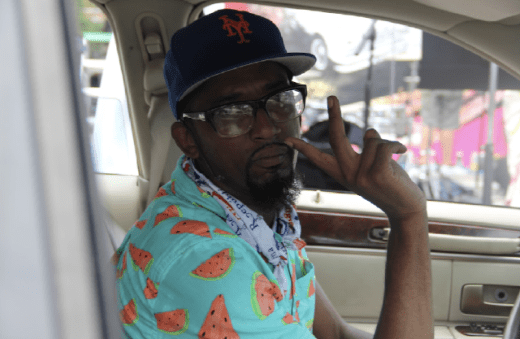

Walking through Bushwick for the first time, I don’t feel lost. Modesto Flako Jimenez, a Bushwick-raised actor, playwright, poet and educator, is my guide through the neighborhood as he sees it, text by text. He sends me photos of his friends hanging out on the corner, and of the way the storefronts used to look. He encourages me to stop walking, to slow down, to look at the outsides of homes and buildings. This narrated-by-text guided walk is just one part of his community-based, multimedia magnum opus on gentrification, Taxilandia. “This is literally like, let’s have a conversation,” he tells me from his car, in his non-stop, rapid-fire style, before I set out. “I am giving you an experience of engagement, and how to properly visit a neighborhood without feeling like your footprints don’t matter here. They do.”

It’s fitting that he’s talking to me from his car. Flako spent nine years as a cab driver, watching gentrification change the scenery and, more importantly, the community. “The landscape is ever-changing, right? That’s a part of the reason why I’m making Taxilandia, but the biggest reason why I’m making it is the disconnect between each other.”

When Flako describes the Bushwick of his childhood, he talks first, and most vividly, about the relationships between people. “The homeless person lived in my hallway, and made a house out of cardboard, and we gave them food from time to time, because we know that was the kid from the woman from the first floor. That was just an addict thing. Issues, but he still deserved food. So that, to me, was the Bushwick back then, right? We will still hold each other down no matter what we were facing in our landscape, right? Disconnects started happening– now the neighbors don’t say hi to each other.”

After moving back to Bushwick after college, Flako saw that disconnect between people grow as the demographics of the neighbourhood changed. “This influx of class and privilege moves in, that just erases all the history that was already here. It was painful, watching my college friends be in my neighborhood and act like they’ve been here longer than me and have more freedom than me.”

Taxilandia consists of four different phases: a series of salons for conversations about gentrification; five pop-up galleries in Bushwick businesses featuring local artists and poets; the $25 Taxilandia guided drive for up to three people in Flako’s car; and the COVID-safe Textilandia guided walk that, for $3, goes right to your phone.

“Everything I’m trying to do has an actionable item always connected to it,” Flako explains, noting that the manufactured, corporate responses to the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor convinced him that audiences needed educating, beyond passively watching theater. Whether that actionable item is providing a coloring book dedicated to informing about COVID with art from local artists, or highlighting businesses in Bushwick with the gallery spots, the purpose is education first. It’s an artistic manifesto for community organizing. With Taxilandia, Flako is providing a way for people to start doing the “real work” by giving back to the community and getting educated, either in his backseat or in the palm of their hands.

Meghan Finn, artistic director of The Tank, a multi-disciplinary non-profit arts presenter and producer, welcomed the opportunity to work with Flako again. “Flako and I did a piece in a yellow cab [seven years ago]. It was maybe a proof of concept a little bit for Flako, but he really has jumped off with Taxilandia as its own incredible experience.” Flako previously co-founded Real People Theater, a company best known for reworking plays by combining some of the language of the original texts with street slang and Spanish, and wrote a show about gentrification based on his poetry collection titled Oye, Para Mi Querido Brooklyn (Listen, For My Dear Brooklyn) that premiered at the Abrons Art Center in New York in 2018.

Phase one: In the series of salons, artists and community members shared what they see in their own neighborhoods due to gentrification. Each salon focused on a different borough, with an artist invited to share photos of their own neighborhoods, and discuss them with Flako and four audience members, who brought photos of their own. Merlixse Ventura, a 25-year-old actress from Washington Heights who took part in the Manhattan salon, described her first time watching the Disney movie Tarzan on the ceiling of her community’s church on 184th and Wadsworth at summer camp as a child. When she came back from winter break at college, she said, “The church was gone…I was looking at this place and I was like ‘Damn, this is the beginning of the end.’” Six years later, as Merlixse showed, all that remains is an empty lot.

Merlixse says that during the salon, discussing those kinds of experiences stirred up different feelings, “from anger, to sadness, to just revealing things to myself that I was saying out loud, that I don’t think I had said out loud, about my experience watching gentrification start to unfold in Washington Heights.”

Phase two: The galleries. Featured businesses throughout Bushwick, like local restaurant Los Hermanos, showcase original poetry, video, and sound design from local artists. The galleries both provide an opportunity for capital for the businesses, and support for the poets themselves, Flako explains. “I’m paying poets to speak on gentrification: How do we bring awareness? How do we put capital somewhere, because it’s needed right now?”

Phase three: The guide itself. Walking through Bushwick with the Textilandia experience, I became hyper aware of my place in the community as a guest of Flako; the church he went to as a child and the afterschool program he fondly remembers. The grocery stores he’s seen disappear, creating a food desert for the locals. The bakery that’s been “giving diabetes since 1945.”

Flako’s texts are tongue-in-cheek reminders that the neighborhood Vogue called “seventh coolest in the world” is actually where people worked each day, where they gossiped on the corners, where they took their children to school. Instead of just passing through an anonymous neighborhood, I became an active listener to the neighborhood itself. Through each text, Flako encouraged me to stop and listen: to peoplewatch in the neighborhood as it existed. Children, families, young men and women, old men and women; instead of viewing the neighborhood as possible real estate, or something defined by its place in the news, I was viewing it as a guest of someone that lived there, and loved it dearly.

Over tacos at Los Hermanos, Flako’s final text reminded me to “Step in the concrete, peep the traces fighting to survive this GEGE beast!” The traces of storefronts, the previous history of the communities that passed through Bushwick before, even the woman selling pig intestines on the sidewalk Flako notes to say hi to in his texts: the fight to survive the gentrification beast looks different on each block, you just need to see it for yourself, or in Flako’s car with him.

Taxilandia isn’t just confined to Bushwick, or even New York. The Oye Group, Flako’s production company, now works with companies all over the country to develop local versions of the piece specific to each city. It’s already begun in San Diego, and the format is something that Flako wants to pass to other artists across the country. “We create that bigger conversation in that gallery of like, ‘Look, it’s everywhere,’ and all through local work. Because it’s everywhere. I don’t need to be the central voice.”

Through each phase of Taxilandia, Flako wants that hard conversation, the feeling of being uncomfortable in discussing something that too often people would rather just inactively experience through art. He wants you to do that real work, and to talk to him about it. “I yearn for that shit; to have a conversation that’s gonna make me grow. I learn through theater, I don’t learn any other way.”

Taxilandia and Textilandia run until May 3; taxilandia.com.

Correction, April 29: The original version of this article was revised because a source misstated the date of the artist’s previous cab piece and because he doesn’t refer to the walking and driving experiences as tours.

Thanks for the story!

We were forced out of Williamsburg after Bloomberg rezoned it in 2005 (along with thousands of other people).

I made a film about what went down.

“Gut Renovation” streams here:

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/gutrenovation